A feature article about S2O Design founder Scott Shipley in Men’s Journal…

Scott Shipley Still Making Waves

S2O Design and Engineering is the design talent behind the world’s most successful whitewater parks. Here is the current whitewater park news from S2O Design.

A feature article about S2O Design founder Scott Shipley in Men’s Journal…

BY PATRICK SISSON

May 7, 2019, 12:47pm EDT

Property Lines is a column by Curbed senior reporter Patrick Sisson that spotlights real estate trends and hot housing markets across the country.

Eagle, Colorado—population 6,500—has mostly existed in the shadows of the state’s massive ski resorts, as in nearby Vail, and its recreational economy. But Eagle, a year-round community for those who work for the big resorts, has plenty to offer, including mountain scenery, a picturesque downtown, and 100 miles of easily accessible mountain biking trails. In spite of all this, it has never become a top-tier destination.

This can be attributed in part to the fact that Eagle never truly took advantage of its natural assets, like its namesake river, which formed the valley that is home to the town today. Fishermen and kayakers have always made use of the Eagle River, but it’s never been a beacon for visitors, despite its high-profile location along the Interstate 70 corridor.

“A stretch of land next to the river used to be a semi-truck parking lot, basically a pee bottle dumping station,” says Jeremy Gross, the town’s marketing and events manager. “It just wasn’t that inviting.”

That’s set to change this Memorial Day weekend, when the town of Eagle will celebrate the opening of a $2.7 million whitewater park locals hope will set off a new era of development in the area, and connect the south bank of the river with businesses and residents downtown. The new Eagle River whitewater park is the result of a multiyear effort to redevelop the river corridor, and will feature a series of artificial rapids, as well as a resculpted, repurposed riverfront, complete with parks and an amphitheater.

It will be the latest example of how smaller towns and cities see riverfronts in general, and outdoor recreation specifically, as new economic catalysts. Former assistant town planner Matt Gross went so far as to call the new park “Eagle’s beachfront.”

“This is just our way of showcasing the asset that we have,” says Gross. “It’s not like we added the river.”

The Eagle River Whitewater Park is part of a growing number of artificial recreation areas, especially in the Rocky Mountains region, trying to capitalize on the nation’s rapidly growing outdoor economy. Eagle believes the new whitewater park can make the town a more well-rounded and attractive destination, furthering the potential of its promising location near mountain biking trails.

According to a 2017 economic study by the Outdoor Industry of America, activities like camping and water sports benefit America’s consumers, businesses, and government at all levels. These activities generate a whopping $887 billion annually—about $702 billion by travelers and vacationers—support nearly 8 million jobs, and bring in just over $59 billion in state and local tax revenue. For comparison, the entire nation’s financial services and insurance industry generates $912 billion.

Whitewater parks—either parks like Eagle’s that resurface and redesign riverbeds to support outdoor recreation like kayaking and rafting, or “pump parks” that create artificial new bodies of water for sport—represent a small part of the nation’s huge outdoor industry. They aren’t new: The world’s first artificial whitewater course, a concrete-channel course called the Eiskanal, was created for the 1972 Olympics in Munich, where the sport made its Olympic debut, and parks have slowly taken root across the western U.S. since the 1980s.

But now that the idea is firmly established, a number of case studies—including an urban development in Reno, Nevada, and the huge boost Charlotte, North Carolina, saw from a national whitewater training and recreation center—point to such parks’ economic benefits. They’re increasingly being seen as a development tool, not just another entertainment option.

In Eagle’s case, it’s a project for and by the community, says Scott Shipey, CEO of S2O, the company building the park. Shipley, a former world-champion kayaker who competed in three Olympics, says it’s not just a new way to build the sport, but a chance for towns to look at their natural economic assets. The town passed a .5 percent sales tax increase to fund the project.

“A lot of towns have a river running through them,” he says. “In the Midwest, there are dams near towns, which used to power industry, that are rotting away. We can give them an experience they didn’t have before. Just by doing a little bit of manipulation of that river, they can become the Breckenridge of kayaking. These mining and ski towns are starting to leverage this resource.”

Designed with Rapidblocs, a patented S2O system that allows for adjustable riverbeds and rapids, the Eagle Whitewater Park will feature spots for kayakers, rafters, tubers, and even surfers. The waterfront, now filled with parkland and public space, can host festivals and concerts, a big potential boost for businesses downtown.

“Economic development is a slow-moving ship,” says Gross. “Now, with a river park close to town, we’re hoping that increase in business brings the next business to town, and then a few more people, and then suddenly, there’s more development connecting the river to downtown. The river is a big thing we have to offer, it’s a piece of the pie.”

The renewed push to repurpose riverfront property in more rural parts of the country mirrors what’s happening in urban areas like Brooklyn: With heavy industry and factories gone, games, recreation, and public space have taken their place—and become magnets for people and economic activity.

Projects like Eagle’s also come as community-building investments in culture have shown their value to smaller cities and towns, the anchors of rural economies. Matt Dunne, founder of the Center on Rural Innovation (CORI), says it’s all about bluegrass, beer, and broadband. Rebuilding formerly lively small-town centers with a combination of arts and culture, recreation, startups, and adaptive reuse has proven a winning formula across the country.

Existing projects demonstrate that these artificial rapids can really rev up local economies. In Charlotte, the U.S. National Whitewater Center, which opened on roughly 700 acres adjacent to the Catawba River, welcomes 1 million visitors a year, and supports more than 500 jobs. In Durango, Colorado, the whitewater park on the Lower Animas River generates $18 million a year in economic activity, according to an economic impact studycommissioned by local leaders.

Reno, Nevada, offers one of the best illustrations of how river redesign and urban regeneration can work together. The neighborhood around the Truckee River in downtown Reno had become neglected and crime-ridden (“they turned their back on the river, to keep people inside focused on casinos,” says Shipley). Since the $1.5 million whitewater park opened, the streets surrounding the recreation site have seen a boom in new condos, restaurants, bars, and businesses. A 2007 study by the Reno-Sparks Convention and Visitors Authority found that whitewater recreation attracted 13 percent of the approximately 4.3 million people who visit the city annually.

“There wasn’t much down there before that, but now the downtown river park is a tourist destination,” Ben McDonald, senior communications manager for the Reno-Sparks Convention and Visitors Authority, told High County News.

“There are as many reasons to do this as there are potential parks,” says Shipley. “These parks have millions of dollars in economic impact.”

Shipley says the industry, which has steadily grown since he founded his company in 2005, will see more expansion. In addition to the soon-to-open Eagle project, S20 is also working on projects in Fort Collins, Colorado; Canon City, Colorado; and Boise, Idaho. The company’s Rapidblocs system will be used at the site of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and S2O expects more cities, especially in the Rocky Mountain region and the Midwest, to invest in new parks.

Other artificial water sports sites have become an option: Famed surfer Kelly Slater has a company dedicated to creating artificial inland surfing parks, including a site in California’s Central Valley. S2O is also looking at more surfing options, and plans to install new technology to support surfers as part of its ongoing work in Boise, Idaho.

For Eagle’s Jeremy Gross, the river that goes through his hometown has always had potential. But now, it’s more central to the growing Colorado community’s narrative.

“If I’m trying to sell Eagle to you, we’re a quick two hours to Denver, if you leave after work Friday you can be at Eagle by dinner time, and over the weekend, ride 100 miles of trail, bring a board or kayak and get in the river,” he says. “It’s becoming more of a well-rounded destination. We’re an outdoor adventure paradise.”

S2O Design’s founder and president Scott Shipley was the lead designer of the whitewater park at US National Whitewater Center in Charlotte, N.C. Today, the USNWC is the largest and most profitable pumped whitewater park of its kind in the world. Its design was tailored to maximize commercial rafting across a broad range of user groups and abilities, from Olympic-level athletes to families. The ¾-mile long whitewater park features four separate channels, including a slalom channel for world-caliber races, the world’s highest-volume big water channel, and dedicated options for beginner experiences. The park attracts more than 700,000 users a year, and boats a $37 million regional economic impact. Learn more about the USNWC and Scott Shipley in this case study.

Download here: Case Study: US National Whitewater Center

When London needed a world-class whitewater park for the 2012 Summer Olympics, they turned to a former world champion kayaker to build it, and the company delivered something entirely new when it made a course with the future in mind.

Shipley won the ICF World Cup three times and competed in three Olympics between 1992 and 2000. He subsequently launched S2O to create whitewater parks, both in-stream and pumped, as well as river engineering projects.

Shipley estimates that the company has worked on a total of roughly 150 projects, which are often completed after up to eight years of work, and help towns and cities revitalize both rivers and riverside economies.

For instance, the S2O designed the U.S. National Whitewater Center in Charlotte, North Carolina, which has hosted the U.S. Olympic team trials for whitewater sports, and is the largest pumped whitewater course in the world — generates roughly $22 million a year in income for the city and another $40 million a year in external effects like lodging and dining, according to Shipley.”When you talk to the economic director of Charlotte he’ll tell you that they . . . were a NASCAR and a banking town, and he’ll say, ‘Now, our number-one attraction is whitewater,” he says.

The company has also developed in-stream projects in Durango and Vail in Colorado. Shipley says the Durango Whitewater Park “has about a $9 million economic impact for that town and rejuvenating that whitewater park was a huge thing for them economically.”

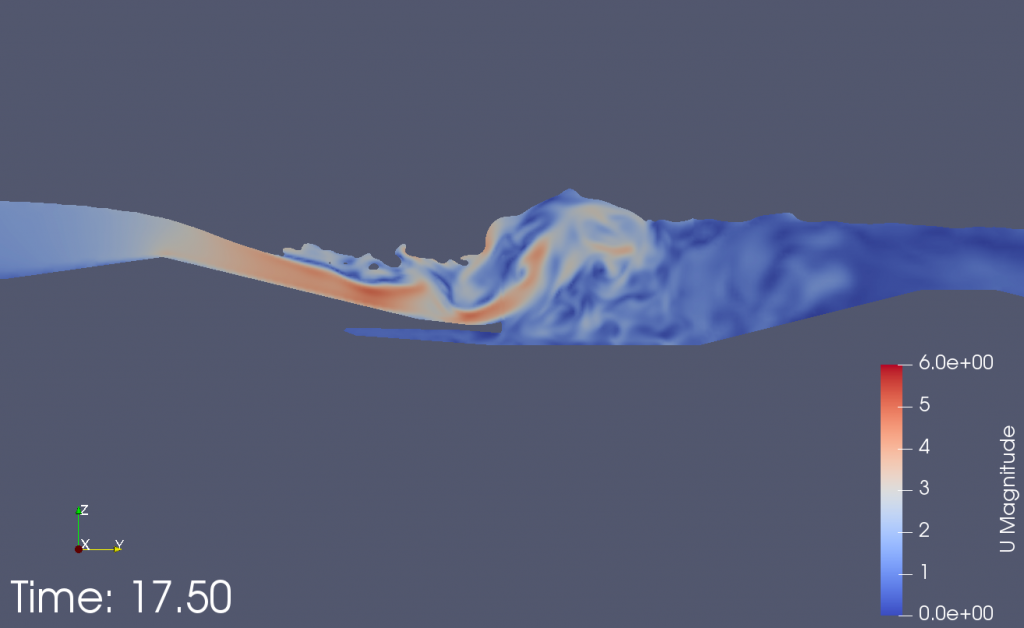

S2O rethought whitewater park design and created the patented RapidBlocs system, which debuted at the London park for the 2012 Olympics. “When we got into designing the 2012 Olympic course, there was some pressure there to meet this objective of having that course be state-of-the-art 10 years into the future,” Shipley says. “So how do you forecast what it’s going to change to? That became the big question. What we came away with was you don’t you you create a course that can change with it.”

Previous designs of whitewater parks would only allow course setters to change about 2 percent of a course. Made by a U.K.-based manufacturer, RapidBlocs are rotomolded polyethylene blocks and shapes secured by standard, 18-millimeter bolts that allow for constant tweaks.

“This obstacle system we made allows you to completely reconfigure a course so that the Olympic course people raced on in 2012, they can go in and change where all the eddies are, and where all the waves are, where all the features are,” Shipley says. “So it allows the course to evolve with the sport. It has is tertiary benefit, you can tune it to exactly what you want. And also you can tune it down, you know later for people like rafters who are going to be want to come out and do easier whitewater.”

A seven- or eight-foot drop-off can be reconfigured into a minor rapid or eddy in less than a day with little more than a speed gun and different RapidBlocs. Shipley notes that if they’re in a water park and people keep having issues at the same feature, designers can quickly change the feature.

They’re now being used in every announced Olympic whitewater park. “They’re just being installed in Tokyo — we actually have a guy over there right now,” Shipley notes. “They have already been installed in what will be the Paris 2024 games course.”

The company also redevelops rivers and streams for flood mitigation projects or to reclaim riparian habitats and the wildlife in them. Shipley encourages communities to take a nature-based approach.

“The river restoration side is a lot of people calling up and saying we analyzed our river, it’s concrete on both banks. We shoved it into it a canal and it’s killing the fish and it’s killing the environment here,” he says. “We can do that restoration and bring the fishing back and bring back the the riparian habitat and at the same time tie that into a recreational master plan that allows for stream-side access.”

Customers often come to S2O with projects on existing dams; they want fish and recreational passage, but want to keep the dam. “That’s an ideal scenario for a whitewater park,” says Shipley. “We’ve got a couple of those were doing right now and they’re fantastic projects because if you’re solving a ton of problems.”

Shipley estimates that the company’s breakdown of projects is roughly about a third in each category: whitewater parks, in-stream whitewater parks, and flood and other river engineering. “That distribution changes from day to day. We’re doing a lot of public stuff right now, but at the same time actually we’re building a lot of in stream right now, and we’re designing a lot fun stuff. And so it really evolves from one to the next.”

S2O is evolving its approach to building whitewater parks to how people are recreating. That includes paddle boarding and river surfing. “We’re coming out with a bunch of new RapidBlocs designs that will allow us to put in standing surf waves for surfers on rivers,” says Shipley. “That’s been a big challenge for us and we’re spending a ton of money on that and doing a bunch of research on that kind of out of our own pockets. In this industry that’s never happened before.”

Challenges: “We are evolving in a way designed to match how the use of these parks changes,” says Shipley, noting that will include the development of new RapidBlocs offerings.

Opportunities: Growing the whitewater economy. “We’ve learned that the casual user will come and go rafting and go,” says Shipley. “But if you can create a resort experience around it, they’ll come, go rafting and then they will go to the restaurant and they’ll rent that cabana and they’ll start to try some of the other activities like zip-lining or climbing walls, and mountain biking, things like that. Then we draw them into an all-day experience which is all about healthy active outdoor lifestyles, and so for us, those are kind of two things that we’re really pushing.”

Needs: “There’s a really uncomfortable growth from 10 [employees] up,” Shipley says. “Right now, frankly, we’ve got so many projects that we kind of got our heads down on a bunch of this stuff and are just working away at it. I suspect when we get a little more breathing room, we’ll attempt to think about some of those things.”

Randy Wyrick

Vail Daily

January 9, 2019

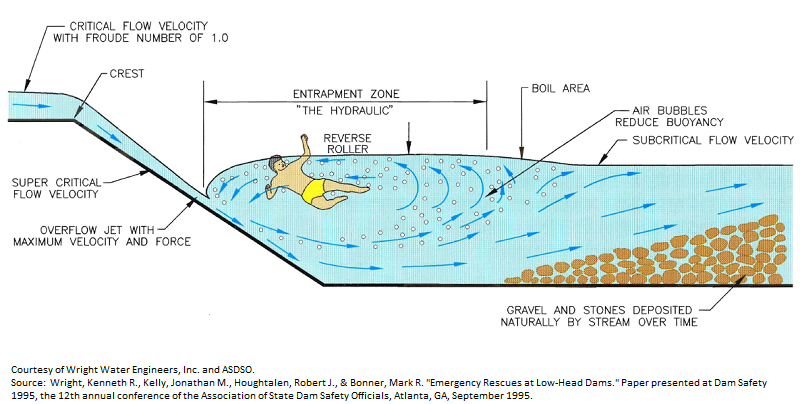

Safe Navigation at Low-Head Dams can be a challenge. Many of these dams have had significant safety issues involving people flowing over the dam and into a keeper hydraulic that led to fatal results and dangerous rescues. Until recently, these dams, which often reside in towns and cities that once relied upon them for cheap energy, have been an unmitigated risk. However, S2o Design and Engineering has begun redesigning low-head dams to create a safe boater bypass, and often the resulting design creates attractive recreation.

Dams provide energy, water, and can mitigate flooding, but, unless they are designed correctly, dams can be hazards to in-stream recreation and a barrier to fish passage. Some of these dams, such as the Bow River Weir, have killed or injured more than 21 people. These features are virtual drowning machines. The unfortunate reality of these dams is that many of them were built early in the 20th century and few of them are designed with recreational boating nor kayakers in mind.

S2o Design and Engineering has been working with many clients to improve the level of safety at these dams. S2o works to either help remove the dam, if it is no longer needed, or to preserve and reinforce the dam while creating recreational rapids below the dam in lieu of the dangerous keeper left in the original design. S2o’s clients include everyone from small diversion dams, such as the Supply Ditch, for which we completely redesigned and rebuilt their dam, to Duke Power, who is building a large boater bypass on a 14’ high dam in the Catawba River.

The purpose of these projects is to create a navigable river, where people who are qualified and equipped to be out paddling are able to navigate the weir or low-head dam without fear of being pulled under. We work with the client to ensure that a proposed solution meets their budget, is appropriate for the environment in which it is placed, and provides for safe navigation.

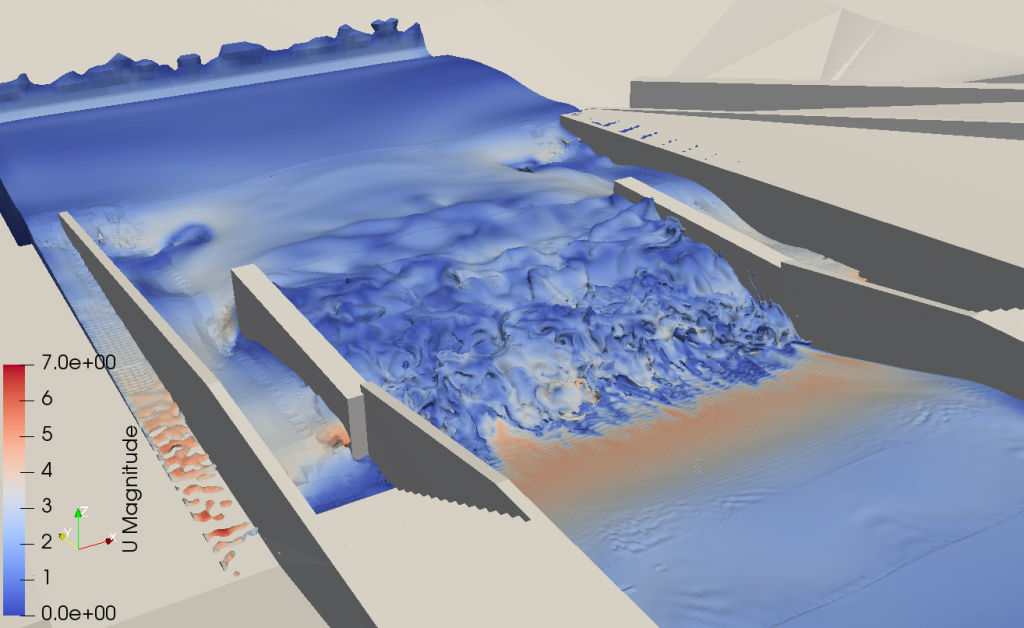

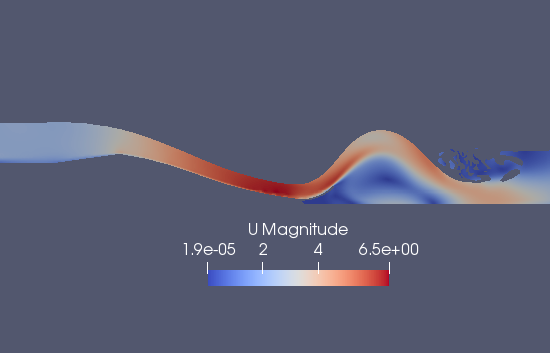

S2o Design and Engineering designs these bypasses several ways. The process can include anything from detailed physical modeling as we did for the Catawba Dam in South Carolina and the Bow River Dam in Calgary, AB; three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics modeling (CFD) as we did for the Thurman Mill Diversion in Boise, CO; or through known geometry and one and two-dimensional modeling as we did for the Lyons Ditch Diversion, the Supply Ditch Diversion, and the Pueblo Whitewater Park and Diversion project.

One of our most common tasks at the outset of a whitewater park project is to initiate the effort with a Conceptual and Feasibility Design Study

My name is Dusty Stinson—owner and founder of Coosa Outfitters in Gadsden, Alabama. Our outfitter’s store has the distinction of being the best place to buy whitewater boats and equipment in the “Store not near Whitewater” category. We are located just off of interstate 59 and have a thriving business in spite of the fact that there is no whitewater in this town today. I believe that our existence alone showcases the opportunity to create whitewater in this town. We already know that whitewater people come to Gadsden; I want to build a whitewater park here so that they will stay.

Gadsden is a former steel-mill town. We’re the type of place in which you would least expect to find a whitewater park. People here are traditional and our economy has historically been based on traditional means. Now that the steel mill is gone things are changing in Gadsden—we are proud of our heritage as a manufacturing center but would also like to evolve our economy to the realities that now surround us. One of the ways I’d like to do this is to develop a whitewater park that showcases our Town’s history and that draws people into town to learn a little bit about us and maybe drive our economy a little by staying in a hotel or eating in a restaurant.

I worked with my Town to try and find funding options for the project through a number of differing avenues but, to be honest, a whitewater park is a new concept for most folks here and it was hard to gain traction. In the end I read about Scott Shipley at S2o Design in a magazine and began to work with them to see if they could help our project develop a vision and get off the ground. Gadsden was willing to foot the bill for a site-visit and concept design study and Scott flew out to meet with myself, the Town Mayor and Town Manager, and the local Tourism Director.

Within six weeks S2o had identified a site, developed a concept design, project cost, and report that described the challenges and opportunities for the project. This information mapped the way-forward for our project by giving me something I could speak to—here is what the project looks like; here’s what it does; here’s what it costs; and here’s how we get it moving. This was something that we could use to get the project off the ground.

The design that S2o used was also highly innovative. S2o chose a site that was at an existing dam and created a design that would leverage the energy there while providing for fish passage and improving navigation on our creek. The site also had ready-made raw materials to create access, parking, and streamside amenities. My favorite part of the project was S2o’s suggestion—and architectural rendering—that utilizes the old pump-house located at the dam as a possible future vendor operation. This was exactly the kind of design that would drive visitors to come of the Interstate and experience both the whitewater and a piece of the town’s steel working history.

The in-stream design was also innovative in that it uses adjustable obstacle systems to tune the wave for varying flows. I needed a park in town that would work at low flows for tubing and lessons and at higher flows so that people would come here to boat when the surf was “up”. This high-tech solution met all of these requirements and more.

Dusty Stinson

Coosa Outfitters

Recommendations:

Work with your local town or city to get these things started. Its something that is going to benefit everyone and having your City on board from the start is going to avoid a lot of heartache later

Your first objective is to get this Conceptual Design Study done. The last thing you want to do is be in the Mayor’s office or a town council meeting trying to sell a project that is completely abstract—you need a plan, a cost, and a route to completion.

Understand your users and design to them—S2o did a great job of this, they understood our Town and so leveraged our Steel-mill Dam and Pumphouse to showcase our history, they understood that we would draw people from the highway who were not yet boaters so designed for tubing and rafting, and they understood we wanted whitewater for the expert as well as beginner so innovated an adjustable design.

A write-up from one of S2o Design’s happy whitewater parks users. We’ve heard from many different users who ended up loving a whitewater park:

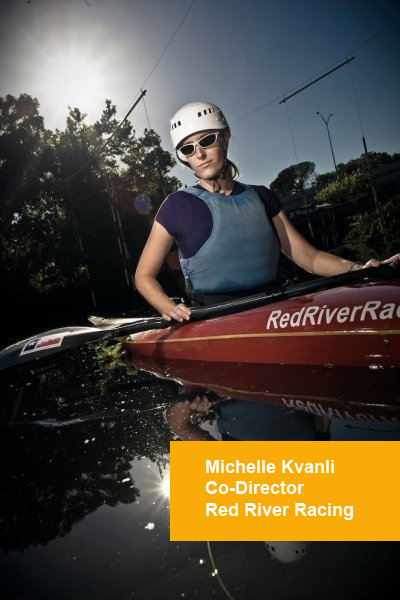

I’m Michelle Kvanli, one of the founders of Red River Racing in San Marcos, Texas. We are a non-profit organization that works to get people into kayaks—some for the purposes of going on to be champion racers, some for the joy, challenge, and therapy (yes therapy) of being in a kayak. We run trips around the country and internationally, but base out of San Marcos. Our property abuts the San Marcos river just downstream from downtown.

The Rio Vista dam has always been a high-point of our program. It was a simple single drop structure until it failed in 2006. We called our friend Scott Shipley, now of S2o Design and Engineering to come work with the City to fix the dam and preserve our best whitewater. S2o did more than that and created an all-access whitewater park that is used by thousands of people every year. These folks swim, wade, inner-tube and kayak at the site on a daily basis. In fact, the new park was seeing so much additional usage that they added lights so we could paddle at night.

The park has had a tremendous effect on our program and on our town. We now have slalom gates at the Whitewater Park year round. This has allowed us to host national-level slalom events such as the 2008 Olympic Trials qualifier. It has also supported a growing group of active racers that use the site. We also have play boating and surfing at the park. The draw from this park has had a tremendous effect on our town. Talk about economic impact! The park is used by so many people that the City hired additional rangers to help monitor the crowds.

The park has also allowed us to play a key role in the Wounded Warrior Program. Red River works with returning vets who have been injured or who are still working to integrate themselves back into being home. We work with them to get them into boats and challenge them—both on the water and off—in an effort to help them find some stability in their own lives. This is a very exciting program both for our City and our Country so I am excited that the San Marcos Whitewater Park allows us to make this happen.

–Michelle Kvanli, Co-Director, Red River Racing

Recommendations:

Bring in a designer like S2o who will think of your park holistically—not just as a whitewater park. Scott’s work to remove the concrete walls and create access for people of all ability levels adds a lot to how this park is used.

Design for all types of visitors—not just top level kayakers.

Create spaces for events and for programs—these are what provide the most impact to your “dry side” community!

Welcome everyone to your park including the inner-tubers and waders and BBQ’rs. This is not just about top level niche athletes!

Physical Modeling of Hydraulic Structures

S2o specializes in the physical modeling of whitewater parks and the Physical Modeling of other Hydraulic Structures. Here is a summary from one of our clients about the Physical Modeling of the London 2012 Olympic Venue at the Lee Valley Whitewater Centre:

Physical Modeling of the London Whitewater Canoe Slalom Venue

I own and operate an engineering firm in the United Kingdom. Ostensibly, I would be a competitor to S2o as I also plan, design, and implement whitewater parks. Instead, however, we tend to partner on projects around the world. S2o’s business model, much like my own, is unique. We are engineering firms that are formulated to fit seamlessly within a larger design team. On many of our projects we team with local site/civil engineers as well as contractors, electrical engineers, architects or whatever the case may bring. Our role—and one that S2o manages very well as well—is to make that larger team stronger and to bring unique expertise in white water design.

S2o and I have worked together on several projects including the London Olympic Park located in Lee Valley near London. The London Park was a rush project as, by the time we became involved, construction had already started and design work had lagged. What was needed was a two-part team, one to manage the project from the UK side—going to meetings, understanding client needs, and coordinating deliverables. From the other side we needed hard data and we needed it quickly. We needed computer and physical models that would substantiate our design and design changes and we needed tools that would convince the Olympic Development Authority and its stakeholders that these whitewater channels would meet, or exceed, their specifications. What we needed was a professional design team that was going to get this job done, and done accurately and quickly.

As a team we hit the ground running and worked seamlessly to create what has been universally called the “best, and most modern, whitewater park in the world”. S2o’s design process, advanced software, and modeling techniques meshed seamlessly with our own such that, though we live on opposite sides of the Atlantic, we were able to collaborate effortlessly. Within three weeks we had created the necessary computer models to show the client that we needed a physical model, within six more weeks we had designed and built the world’s largest physical model ever constructed for a whitewater park. It was a 1:10 Froude Scale model constructed at S2o’s facility in Boulder, CO (USA) and it gave us a place where the British Canoe Union, the Olympic Delivery Authority, and other stakeholders could wade into the future Olympic Channel and measure and evaluate the velocities, the waves, the eddies, and other whitewater characteristics with their own hands. That one model was all it took to move a project from stalemate, to approved design by all parties. Within 12 more months we would paddle on that same course as it was being approved by the International Canoe Federation for competition for the next games. This was a project where the Physical and Computer Models—and the professionalism with which they were made—defined the project.

Recommendations:

Start with the best design team you can find—one that has completed projects accurately, on time, and to the expected standard. You don’t want to change mid-stream and expect a rush job.

All great whitewater parks are team efforts. You need to pick a whitewater design team that works well as a team. The best metric of this is “how many projects have you finished recently?” If they’re getting projects done, they are good teammates.

Etc.

Part of the process: Michael Williams, Design Process

A quick discussion from Michael Williams about the process of Designing Whitewater Parks.

Liquid Design was the project lead for the design team on the Charlotte Whitewater Park. We were directly responsible for the project management and coordination of over 24 various consultants and specialty consultants for the design and construction administration of the U.S. National Whitewater Center located in Charlotte, North Carolina. We were also the master planner for the 350 acre site and the architect of record for all building structures.

These projects are mammoth undertakings. Project management is the key element. You must have someone efficiently guiding the process that has experience in leading it and you need team members that can work as a part of that team—doing their part on time and helping the remainder of the team to do their parts. The reality of this project type is that not everyone truly knows what the end result will be. For example the Pump consultant is good at what they do on a daily basis—they move the water from the bottom pond to the top. However, they really don’t understand what that means when you have to use the pump system to move over 1,000 people on rafts. That is why experience in this project type is so critical. This process is about understanding the holistic design solution and ensuring that the client gets what he’s paying for that is so important.

One consultant that you do not want designing in the dark is the whitewater engineer. That is why S2O was a key part of the process and a part of our lead design team. They understood the holistic design solution and exactly how the whitewater components fit into it. From day one they helped shape and mold design decisions that made the product better. Their high-tech team provided not only drawings that actually could be built but their design solutions worked, critical for clients who are ready to start producing revenue. Also, their use of state-of-the art and industry standard software allowed us to share design documents so that final assembly was easy, accurate and timely.

I was so impressed with S2O’s work ethic and creative vision that when they ask me to join their global team I signed up without hesitation. It didn’t hurt that I love this unique project type and working with S2O allows me to work with talented individuals who share this same passion.

Michael Williams

Liquid Design / S2o

The Future for Whitewater Parks, both in-stream / river diversions and man-made “superparks”, is bright. The following is a small list of what I think will be key elements for future whitewater park development;

Uniqueness: Just by the nature of competition the parks will have to have the longest, fastest, and biggest of something for customer retention.

Discovering the Uncompahgre River Corridor as a community amenity

S2o has led, or has been a team member, on a number of river corridor master planning efforts. These projects serve to plan a corridor respecting the river’s natural morphology, and the habitat that it fosters, and serves to integrate the community with this river in a way that allows for recreation, access, smart development, and the preservation of beautiful natural areas, amongst other priorities. This is the story of one of our projects as told by the team we worked with:

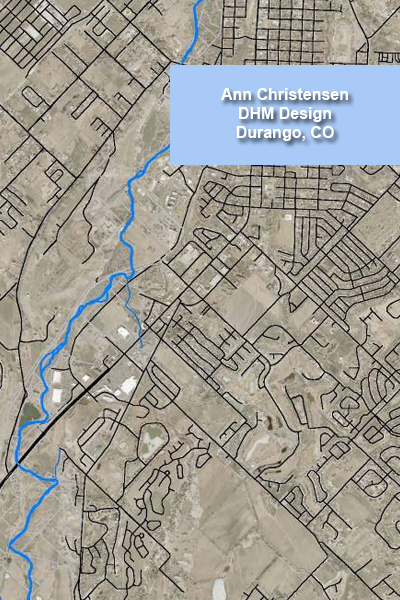

The City of Montrose is located along the Uncompahgre River. Historically, this City supported agricultural and industrial land uses. To this day, gravel mining, for example, remains a significant source of income, supporting the growth of surrounding mountain towns and resorts. Over the past decade, commercial and residential housing developments have in-filled closer to the river, largely isolating the river from public access. Montrose responded to community interests in protecting and enhancing the Uncompahgre as a public amenity by investing in planning with the support of Great Outdoor Colorado lottery funding. Currently, the river is only occasionally floated due to limited public ownership of the adjacent property and lack of access points. Montrose is just a pass-through for those visiting the famed M-wave on the Gunnison River outfall. Our project was tasked with improving public access and usage along this river corridor.

As a landscape architect and principal with DHM Design, I led the effort to prepare a master plan that describes a vision for the future of the Uncompahgre Riverway through Montrose by building on the existing natural characteristics, urban connections and broad community support. I hired Scott Shipley to examine the potential for the river to host whitewater activities. Scott found that the river characteristics support a variety of potential features and that the flows regulated by releases through the upstream irrigation system and reservoir provide consistent levels late in the season when many other rivers are low. Our team was also augmented by Walsh Environmental for ecological assessment and RPI Consulting for community input facilitation.

Scott provided a well attended presentation of whitewater parks around the world and the benefits they bring. The Montrose community showed tremendous interest in having their own whitewater park, not only for their own recreational use, but for events and spectators. Montrose supported the idea of a whitewater park drawing tourism and awareness of the larger river corridor as part of their identity. After examining the corridor with us, Scott described a number of possibilities ranging from family friendly tubing features to a competition worthy challenge course.

Master planning for a community is not easy—it can be especially difficult when including a dynamic amenity such as a whitewater park. These parks have the potential to host extremely well-attended events. As a potential draw to many people, each chosen location must fit within the community infrastructure, anticipating the need for vehicle and pedestrian access, parking, and restrooms. River banks can be enhanced to provide paths, hardened points for access and informal seating through the deliberate placement of boulders. Within the larger community, Montrose is particularly interested in providing a draw that supports river oriented cafes and retail shops.

With many features possible, the challenge is bringing them within reach of tight budgets. Our team identified an ideal opportunity by selecting an existing park to include our future Whitewater Park. In this way, with relatively low investment, whitewater elements could be introduced without re-investing in infrastructure and parking. This locationquickly gained the benefit of greater visibility and increased tourism that would in turn support additional investments. As part of a collaborative effort, the master planning process started discussions with the water district, Bureau of Reclamation, City engineering, and other agencies that have the potential to partner for the replacement of aging structures in a way that weaves whitewater features into a solution that will have many benefits for this little City that reach far beyond the scope of creating a simple play-wave.

Lessons:

Design of whitewater parks must consider potential impacts to the surrounding community in terms of traffic, access, parking, and public access.

By drawing attention to the whitewater features, awareness of the entire river corridor is gained, supporting investment in the overall health of the river system.

Partnerships hold great potential to bring whitewater elements within reach with cost sharing.

Collaboration with the widest range of river stakeholders is critical to gaining support for a successful project.

I initially contacted S2o Design and Engineering about helping me to create a vision for a pumped Whitewater Park in the Southwest. We accomplished this task with such a large degree of success that it has opened a tremendous can of worms down here. The site plan created by S2o is so attractive that we literally have people from the surrounding Towns and Cities trying to get us to move our project to their location. S2o identified our customer base and designed a profitable concept around our target audience—this is a project that everyone in our region believes is a clear success.

We are now in the process of working with our local City to try and solicit funding for the project. We are targeting funds from a variety of sources including local government support, state and federal grants, and investor financing. We expect our final funding portfolio to be a mixture of these options.

As a part of the process of soliciting funding we have needed to know three key elements related to the economic impacts of whitewater parks:

The first question was, “how many people in our area like to raft and how many of these folks are likely to come visit our site if we build this thing?” In order to understand the answer to this question we commissioned a Market Analysis from S2o Design and Engineering.

The second question we needed to know the answer to was, “If the expected number of people show up, will our venue be profitable?” In order to understand the answer to this question we commissioned S2o to undertake a Business and Market Analysis.

The last question we needed answered is, “how will the visitors that come to my park affect the economy of the surrounding city and region?” Our host City wanted to understand these effects so that they could judge how much they were willing to contribute to making this project happen. In order to address this question we had S2o undertake an Economic Impact assessment.

We had a lot riding on the results of these studies and were being held to a very high standard. The State commissioned a large and well known independent accounting firm to review our business model and market analysis prior to analyzing our grant application. This accounting firm not only reviewed the numbers but applied several sensitivity tests to see how robust the business model was in the face of lower attendance or lower price point. S2o’s Business model and market analysis passed with flying colors. The accounting firm did not suggest a single revision.

The economic impact study did even more for our case. Again, it was a well documented study based on actual user data from our region. When the City’s economic team took it apart—checking the source data for content and validity and applying their own analysis to check our results—and came back with the same comments as the state: “it looks good”.